- ABOUT US

- INVESTMENT FUND

- PARTNERSHIP SERVICES

- IMPACT INITIATIVES

-

SPACES

- HONG KONG

- Co-working space

- Event Space

- Prototyping Lab

- LONDON

- Co-working space

- Event Space

-

FABRICA X

- HONG KONG

- Campaign

- Events

- Online Store

- LONDON

- Exhibition

- Retail

- Subscribe

Following our previous post on methane—what it is, how its emissions differ from CO₂, and why addressing them matters—this article aims to put the spotlight on innovative solutions emerging today. While reducing beef, lamb, and dairy consumption offers the most straightforward path to cutting methane emissions, the focus here is on the agrifood system (where ruminant livestock and rice production are primary sources) and efforts to remove methane already in the atmosphere.

Livestock Methane Emissions

Ruminant livestock, especially cattle, but also sheep and goats, emit methane as a part of their digestion. It’s hard for animals to digest the fibre in grass, so ruminants rely on bacteria living in their stomachs to break it down into a form they can use. The bacteria make nutrients for the cattle, but some of them also produce methane as a byproduct. The cattle can’t use the methane, so they burp it out, and it contributes up to 32% of global methane emissions1!

Innovators are exploring various ways to reduce the amount of methane emitted by livestock. The main ways to do this are either to block the bacteria in their stomachs from producing methane or to shift the balance of bacteria towards those that produce less methane. The first breakthrough came when a team in Australia discovered that feeding Asparagopsis seaweed could reduce cattle methane emissions by over 90%. Since then, startups such as CH4 Global, Symbrosia, Sea Forest, and SeaStock have developed various formulations of Asparagopsis-based feed additives. The main active ingredient in the seaweed is a chemical called bromoform, so startups like Rumin8 are using bromoform directly in their formulations.

These additives work well for animals raised in feedlots, but grazing animals, which might not have a single consistent feeding site, need a long-lasting solution. Number 8 Bio has developed a non-bromoform compound that can be formulated to remain in an animal’s stomach, continuously reducing methane when cattle are out to pasture. ArkeaBio and Lucidome are working on vaccinating cattle against methane-producing bacteria, so that their bodies will naturally fight them off.

Other startups are working on masks that siphon off methane from cattle, developing probiotics to shift the balance of their microbiomes, or even breeding new types of cattle with lower emissions. Reducing agricultural emissions is critical to meeting our climate goals. As long as people continue to consume beef and dairy, it is essential to produce them in a lower-carbon way.

Image: picture via Canva.com

Methane from Rice

Rice provides 20% of all calories globally and is a staple food for most the people on the planet.2 Unfortunately, it also produces around 10% of all methane emissions. Unlike with beef, it’s not as simple as asking people to eat rice less often, so it’s important to spread the word about low-methane rice growing strategies.

Methane is produced by soil bacteria when rice paddies are flooded. The key to reducing methane production is to change planting and irrigation patterns so that the paddies are flooded for shorter periods.

These strategies work just as well as traditional ones, but many farmers are reluctant to take the risk of switching over. Startups like AgriG8 and Rize teach farmers about low-methane farming practices and provide financing or reduced-cost seeds and fertiliser to incentivise them to implement them. Mitti Labs and CarbonFarm combine farmer education with in-field and satellite measurements to verify changes that enable the sale of carbon credits. At the end of the day, we know how to grow lower-carbon rice—the trick will be spreading the practices as broadly as possible.

Image: picture via Canva.com

Methane Capture and Usage

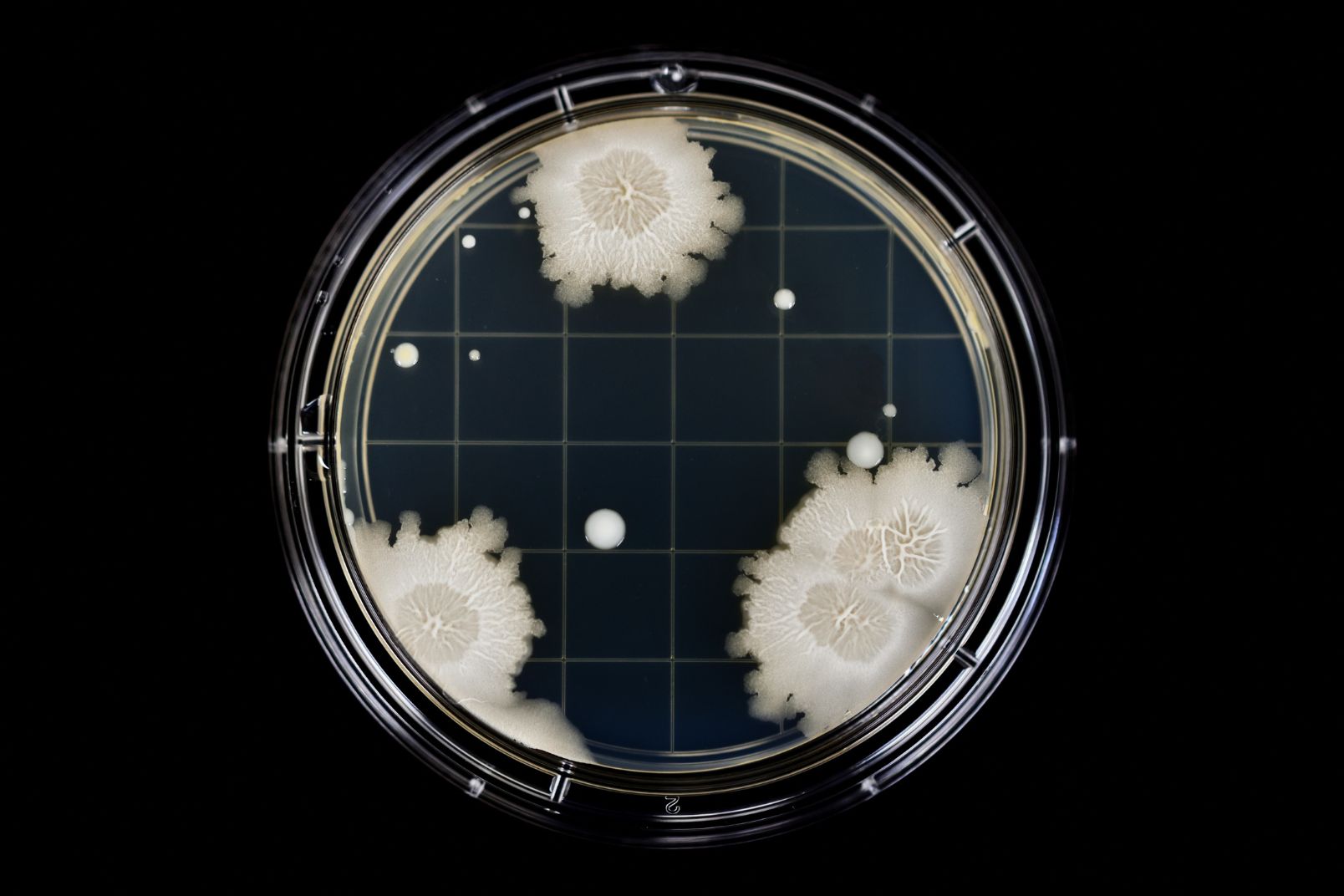

In addition to reducing the new methane we’re adding to the atmosphere, we can also find ways to remove existing methane from the atmosphere. Similar to carbon capture and usage technologies for CO2, we can pull methane out of the air and use it as a building block for functional, carbon-neutral materials. This can be done by using chemical catalysts that convert the methane into other useful substances or by using methane-eating microbes called methanotrophs. Since methane is usually present at a low concentration, this technology works best to capture methane being produced or released by a single, localised source.

For example, our portfolio company Mango Materials grows microbes that eat methane and produce biodegradable plastic. They collaborate with methane producers like landfills and wastewater treatment plants to capture methane and feed it to their bacteria. This plastic can be used as a carbon-neutral component of garments like the Allbirds M0.0nshot Zero.

Image: picture via Canva.com

Methane may be less well known than its cousin CO2, but reducing methane emissions is a vital part of our strategy to fight climate change.

Methane emissions come from many sectors, including energy and waste management, but here at The Mills Fabrica, we’re starting in the agrifood sector. We’re partnering with DFI to help discover solutions to decarbonise their beef and dairy supply chains. Find out more about the DFI Sustainability Innovation Challenge and how you can apply: https://www.themillsfabrica.com/events/dfi-sustainability-innovation-challenge/